It took several hundred million years after the formation of Earth some 4½ billion years ago for the initially fiery globe to cool down, allowing the first oceans and land masses to form. The land was barren rock for the next three billion years.

The blue planet with green continents that we know today did not exist as such in that era. For conditions on the continents were largely hostile to life, with a much higher volcanic activity releasing toxic gases into the atmosphere, a weaker magnetic field than exists today exposing the land more to cosmic rays, and a thinner ozone layer to filter out UV light.

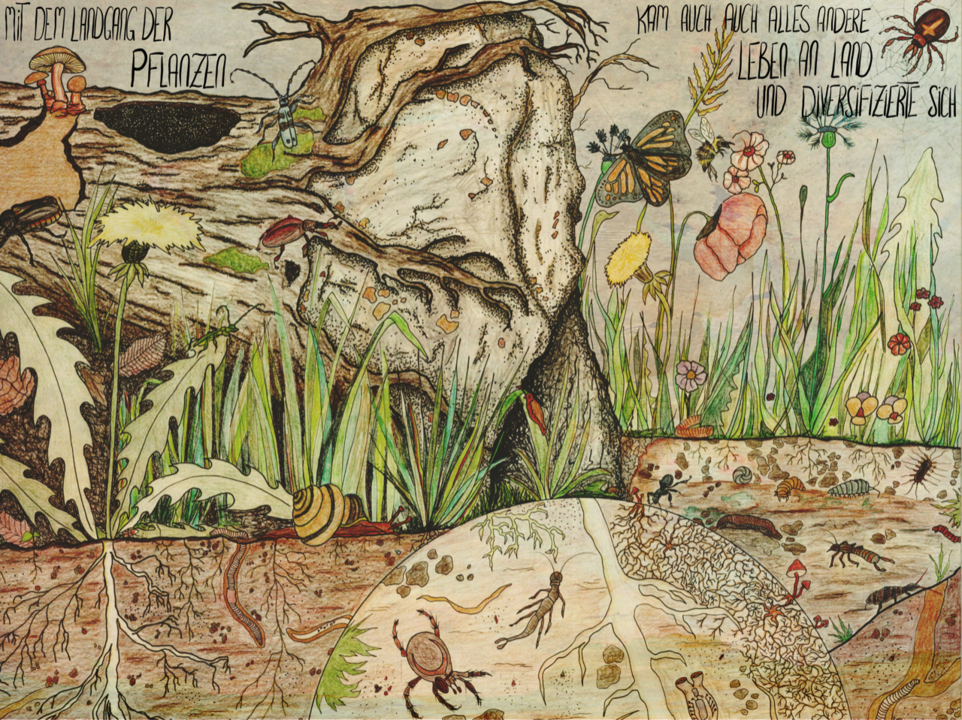

This started changing approximately 500 million years ago when plants began colonizing land. The invasion catalysed a metamorphosis of the hostile environment, accelerating the transformation of the atmosphere, to lay the foundations for the development of life on land as we know it today. All this could only occur once plants, which had only lived in the oceans and inland freshwater, had conquered the continents.

Now Prof. Dr. Sven Gould of the Institute of Molecular Evolution at HHU, Prof. Dr. Stefan Rensing and Dr. Mona Schreiber, a bioinformatics specialist and artist from the University of Marburg, are providing an overview of the current state of research on the plant colonization of land in the journal Trends in Plant Science. Their paper was written in connection with priority programme 2237 “MAdLand” (Molecular Adaptation to Land), funded by the German Research Foundation. The purpose of the MAdLand programme is to explore the beginnings of the evolutionary adaptation of plant organisms to life on land.

The continents only began turning green after a streptophyte alga moved from an aquatic habitat into shore zones before completely transitioning onto land over 500 million years ago, in a process involving numerous molecular and morphological adaptations. Throughout Earth’s ongoing changes, plants demonstrated tremendous adaptational capability and altered the climate in crucial fashion, chiefly by fixing carbon dioxide (CO2) on a massive scale.

Terrestrial flora spread in a dominant tour de force, with flowering plants proliferating in explosive fashion; today they comprise over 90% of all known terrestrial plant species. In the history of our planet, land plants have caused several climatic changes, demonstrating tremendous adaptive capability again and again.

Researchers are studying the genomes of species of evolutionary significance with regards to terrestrialization, including mosses, lycopods, ferns and certain algae, in an effort to advance our knowledge of evolutionary processes and molecular adaptation. Their work aims at identifying the mechanisms that served to mitigate hostile life conditions on land, which changed in the course of this evolution. These may indeed prove relevant with regard to climate change, including for crop modification in response to shifting environmental conditions.

Regarding the role of humans in the planet’s evolution, the study’s senior author Professor Gould elucidates: “Human beings, which have but a brief history compared to plants, are indeed responsible in their own right for significant changes to the planet and its climate. The extreme rapidity of those changes poses a major problem, as nature has insufficient time to adapt. The pace of human-caused change accelerated when man developed agriculture and animal husbandry, which led to steady population growth and the clearing of ever more land for farming.” In this work the collaborating authors analyse human influences on the climate, discussing the adaptability of plant life to the changes that are today unfolding.

Original publication

Schreiber M, Rensing SA, Gould SB, The Greening Ashore, Trends in Plant Science.

DOI: 10.1016/j.tplants.2022.05.005